|

The dictionary defines a march as "a piece of music composed to accompany marching, or with a rhythmic character suggestive of marching." This definition captures the origins of the word and genre...essentially, music designed to move bodies in coordinated steps or stepwise motion, whether in military formations, ceremonial processions, or even funeral rites. Over time, the march has evolved beyond its original functional purpose, becoming a distinct musical form. While composers of the past century may not have envisioned soldiers or parade bands when writing marches, they certainly emulated the distinct stylistic characteristics set by their predecessors. Indian Military Band March NATIONAL MARCH STYLES Many countries have developed their own distinctive, unique body of march literature, influenced by and reflective of the cultural and societal identities of their countries of origin. These marches not only embody the musical traditions and stylistic nuances of their respective nations but also serve as historical and patriotic expressions. Whether used in military processions, civic ceremonies, or concert performances, national march styles often incorporate characteristic rhythms, harmonic structures, and instrumentation that align with the broader musical heritage of a region. For example, British marches exude a sense of grandeur and measured dignity, German marches emphasize precision and power, and Spanish marches carry an unmistakable flair with their lively rhythms and expressive melodies. The evolution of these styles reflects not just musical development, but also shifts in national identity, military tradition, and cultural pride. British Marches British marches tend to have a dignified, unhurried quality, with intricate countermelodies and broad, lyrical lines. Kenneth Alford (whose real name was Frederick Joseph Ricketts) is perhaps the most widely performed British march composer, known for Colonel Bogey, Army of the Nile, and The Vanished Army. Other British marches of note include The Dam Busters by Eric Coates (originally written for a film soundtrack), and Royal Air Force March Past by Walford Davies. German Marches German marches are typically more rigid in tempo and structure, often featuring a strong polka-like feel due to their characteristic "oom-pah" patterns in the low and mid voices. Their final strains often boast a powerful, lyrical melody. Classic examples include Carl Teike's Alte Kamaraden (Old Comrades) and Hermann Starke's With Sword and Lance. French Marches French marches stand apart from their European counterparts with their emphasis on brass and percussion, often incorporating a triplet feel and accentuating the downbeat of every second measure. They fall into three broad categories: the Défilé (marching music with heavy downbeat accents), the Marche (performed by bands alone), and the Pas Redoublé (a concert march akin to a symphonic march). Louis Ganne's Marche Lorraine is a fine example of this style, and is often regarded as the quintessential French patriotic march. Camille Saint-Saëns' often-overlooked Orient et Occident is a particular favourite of mine. Spanish Marches Among the most exhilarating to perform, Spanish marches generally fall into three categories: Marcha (military-style), Marcia de Concierto (concert march), and Pasodoble (associated with bullfighting or dance). Composers such as Antonio Álvarez Alonso (Suspiros de España), Pascual Pérez-Choví (Pepita Greus), Jaime Texidor (Amparito Roca), and José Padilla (El Relicario) exemplify this tradition. Not to be overlooked is also the phenomenon of composers of other nationalities writing in the Spanish style, such as American composer George Gates (Sol y Sombra). Italian Marches Italian marches often feature lyrical, operatic melodies contrasted with fanfare-like sections or delicate soprano obbligatos. Prime examples include Eduardo Boccalari's Il Bersagliere and Davide Delle Cese's L'Inglesina. Another distinct Italian genre is the Marcia Sinfonica, a concert march rich in sweeping themes and thematic development, such as Giouse Bonelli's Symphonic Concert March. American Marches American marches typically feature contrasting strains, two or more different melodies, and a "trio" section of strains/"repeats" that offers pronounced contrasts in phrasing as well as a new key area. No discussion of marches is complete without mentioning "The March King", John Philip Sousa; however, there are other significant American march composers of note, including Henry Fillmore, Karl King, and C.L. Barnhouse, all of whom contributed immensely to the lexicon. The Stars and Stripes Forever THE MARCH IN ORCHESTRAL REPERTOIRE From the beginning of its musical life, the march has also attracted the attention of composers of more "serious" forms. Beethoven, Berlioz, Mahler, Mozart, and Tchaikovsky all wrote marches, in some cases incorporating them into their operas and symphonies. This tradition continued with composers throughout the 20th century. Although most of the following marches were not written with a wind band in mind, transcriptions exist for all but a handful, and they are worth getting to know:

*Sea Songs was originally written to be the second movement in Vaughan Williams' Folk Song Suite for wind band. It was later transcribed for orchestra by the composer. Military Band on Parade March WHY MARCHES STILL MATTER Growing up in Florida, I developed a deep appreciation for marches, largely due to the Florida Bandmasters Association’s festival requirements: every performance had to include a march. This exposed me to an enormous variety of marches, from the simple (Ted Mesang's Sturdy Men and Little Champ, Walter Finlayson's Storm King) to the challenging (Boccalari's Il Bersagliere, Chovi's Pepita Greus, Sousa's George Washington Bicentennial). As a high school band director, I came to appreciate, and even enjoy and embrace marches. I valued them for their ability to reveal an ensemble’s strengths and weaknesses quickly. Can the band articulate cleanly? Maintain balance and blend? Adjust pitch in the trio section? Shape phrases musically? The march serves as a diagnostic tool for these essential skills. Unfortunately, I’ve noticed a decline in the appreciation for marches among both students and directors. Many university wind ensembles can go an entire season without programming a single march, not even as an encore piece. Marches are part of our wind band heritage, and neglecting them means missing out on a genre rich in musical and pedagogical value. Although my days as a high school director are behind me, I still endeavour to program at least one march per semester. Marches make great openers, but they also make great encores, especially the old favourites of Sousa. Nothing can get an audience tapping their feet quite like a well-played march can, and I wish more conductors (of every level of teaching) would make a renewed effort to discover marches they may not be aware of. To aid in that endeavour, I present here some of my favourite marches...I hope you will do the same in the Comments section, so that may all learn something new. PERSONAL FAVOURITES

These are a few of my favourites...your mileage may vary, of course, depending on your musical tastes, but these are the ones I've enjoyed conducting (or performing), and can still listen to them with a great degree of satisfaction. Abschied der Slawin (also known as "Farewell, Slava") by Wassily Agapkin A great Russian march, complete with minor mode melodies, and a daunting key signature. There are a few different editions out there, but the Borgoeois one is probably the best. Fits well with a Russian-themed concert. Brighton Beach by William Latham A wonderful little march that was listed amongst the one hundred most popular marches by The Instrumentalist four different times between 1960 and 1976. Features plenty of nice melodic writing, and it isn't all that technically demanding for the musicians. Perfect for honor bands and younger ensembles. British Eighth by Zo Elliott One of my favourite marches, a regal and stately march in the British style (though Elliott was not British). Not terribly difficult technique-wise, but contains enough musical material to keep your musicians engaged. Commando March by Samuel Barber The one work for winds by Pulitzer Prize-winning Samuel Barber. Not your typical march, and quite difficult but rewarding. Hoch und Deutschmeister by Dominik Ertl A great little Austrian march that is not terribly difficult. I've used my own transcription of this march several times for honor bands, as it comes together nicely in a short amount of rehearsal time. National Emblem March by E. E. Bagley One of the standards, frequently confused for a Sousa march. Can be found in several editions. Another lifetime ago, when I was a member of the Phantom Regiment drum and bugle corps, this was one of our corps' signature marches (along with Sousa's El Capitan). March, Opus 99 by Sergei Prokofiev One of my favourite marches from one of my favourite composers. Quirky, fun, and requires a solid trumpet section (or at least a solid duo). Symphonic Concert March by Giouse Bonelli Previously mentioned above, this is certainly not a quickstep march, but rather an Italian concert march full of endearing melodies presented in operatic review fashion. It is a tad on the long side, and is quite challenging on the woodwinds. The World Is Waiting for the Sunrise by Ernest Seitz (arranged by Harry Alford) A tuneful march with an interesting backstory, having been composed first as a popular ballad in 1919, then later adapted for the University of Illinois Marching Band as a euphonium feature, before finally becoming a concert march. = = = In the more recent past, contemporary composers have continued to explore the march’s possibilities, with Don Grantham's An Uneasy March, Julie Giroux's Tiger Tail March, Jennifer Jolley's MARCH!, John Mackey's Xerxes, and Steve Bryant's MetaMarch serving as good examples. I’d love to hear from you out there - drop your favorite marches (new or old) in the comments so we can all discover new gems. Let’s keep the tradition of the march alive in our concert and rehearsal halls!

I consider myself incredibly fortunate to have started my drum corps journey with Phantom Regiment during the early 1990s. None of us could have known at the time that we were witnessing the end of an era, as the pageantry world was about to lose three visionary drill designers whose innovations forever reshaped the activity, leaving a lasting impact on both drum corps and high school marching band drill design.

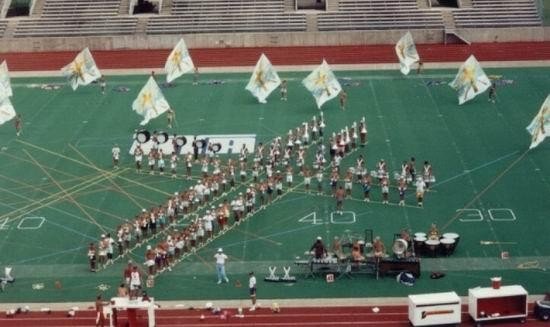

Phantom Regiment 1993, end of Fire of Eternal Glory

John Brazale's journey with the Phantom Regiment began with his work for the color guard, but by 1980, he had taken the reins as the corps’ drill writer. His impact was profound, and even after his passing following the 1992 season, his influence remained deeply embedded in the activity. His work with Regiment, particularly in 1988, 1989, and 1991, was a major source of inspiration for me, and I feel grateful to have been a part of his final two drill designs (1991's Phantom Voices and 1992's War and Peace). Brazale’s ability to craft elegant, sweeping formations that mirrored the emotional depth of the music made his designs effective and unforgettable (the 1989 New World Symphony production spurred me to audition for the Regiment).

Phantom Regiment 1989: From the New World

Steve Brubaker, synonymous with the Cavaliers’ innovative visual style of the 1980s and early 1990s, worked with the corps from 1981 until his untimely passing in 1992. Brubaker helped redefine what was possible in drill design. The 1992 Cavaliers’ show, co-written with Greg Poklacki, was Brubaker’s final contribution, but his mesmerizing, geometric formations had already cemented his legacy. His designs featured angular formations that constantly shifted in visually engaging ways, complex rotating and expanding geometric patterns, and an emphasis on precision and timing, making formations appear to evolve seamlessly.

This style became the hallmark of The Cavaliers, leading them to a steady rise up the ranks during the late 80s, culminating in their first DCI championship in 1992 (and eventual dominance during the 2000s with one of Brubaker’s protegés, Michael Gaines). His 1989 and 1990 designs, in particular, deeply influenced my own approach to drill writing. Watching his kaleidoscopic motion unfold across the field was like witnessing music come to life in a way no one had seen before, and he influenced countless high school marching band drill writers of the 80s and 90s.

Cavaliers 1990: Cavalier Anthems

And then, of course, there was George Zingali, a true innovator whose work with the 27th Lancers, Garfield Cadets, and Star of Indiana was nothing short of revolutionary. His groundbreaking designs shattered expectations of what drill could be, combining dynamic movement with deeply expressive visual storytelling. Drawing inspiration from natural phenomena like water droplets, Zingali’s asymmetrical “flex-drill” techniques allowed for fluid, organic formations and continuous motion, with performers shifting seamlessly between forms rather than moving in rigid, predictable ways.

Zingali’s early innovations culminated in the Cadets’ 1983 DCI Championship-winning show, which changed drill design forever by proving that movement could be as expressive as music itself. His work with Star of Indiana helped win them the 1991 DCI Championship with the legendary Roman Images show, but my absolute favourite drill of his from any point in his career has to be the 1990 design for Belshezzar's Feast.

Star of Indiana 1990: Belshezzar's Feast

The story of 1991’s “cross-to-cross” rewrite is one of those drum corps urban legends that is oft-embellished, with people claiming Zingali wrote the new ending during Finals Week (or, in some tellings, the night before Finals). In reality, Zingali wrote the new ending when the corps was touring in Massachusetts, and it was first performed at the Lynn show, almost a week before DCI Quarterfinals (the old design involved a cross transitioning into a crown set, and then back out to a cross).

Star of Indiana 1991: Learning the Cross-to-Cross

What is not embellished, by all accounts from people who were there (and from what I remember hearing during the season as one of their competitors) is that Zingali taught the new ending without drill charts. He had a vision of how he wanted to end the show, and in a 5-hour frenzy, directed members to their new spots (while visual techs scrambled to chart the new sets on the fly), finishing sometime around 2am that night, cementing an unforgettable moment in drum corps and drill design history.

To that “pantheon” of designers, I could add many more that have come since, who have all influenced my own drill writing in some way: Myron Rosander. Marc Sylvester. Leon May. Michael Gaines. Pete Webber. Jeff Sacktig. Jamey Thompson. Although I no longer design for über-competitive bands, choosing to focus on “show style” or non-competitive high school and university bands, I still use techniques and ideas learned by watching the work of these gentlemen. Reflecting on their contributions, I can’t help but wonder: when will we see more female designers rise to the top echelons of the activity? The art of drill design is ever-evolving, and I look forward to the day when the field is as diverse and inclusive as the students and performers it serves. Although the world of drum corps and marching band drill design has changed drastically since "the days of yore," the activity is still deeply rooted in history. As part of a “Marching Band Techniques” course I teach to university music education students, I delve a bit into the history of the activity, and thought it would be fun to take a (non-comprehensive) look at the history and evolution of drill design. Early Roots

In the United States, the earliest marching bands were university bands, in most cases associated with military ROTC programs. These bands would have emphasized uniformity, discipline, and efficiency. Their "drill" (such as it was) would have been characterized by straight-line formations that moved in block-style units with limited motion, call-and-response maneuvers dictated by the drum major or commanding officer, and was primarily used for parades and ceremonies. Marching styles were highly regimented, emphasizing sharp, 90-degree turns and perfectly measured step sizes.

It is interesting to note that marching bands existed long before they were associated with football halftimes: The oldest University marching band is Notre Dame’s Band of the Fighting Irish, formed in 1845. Their first performance at a football game, however, came 42 years later in 1887! These early bands would have marched in parade blocks and squad formations. At this point in marching band history, true creative drill design had not yet emerged. The earliest example of something other than a squad-based military formation came from Purdue University in 1907, when they produced a "Block P" during a performance of school songs.

Block P - Purdue University Marching Band

That same year, the University of Illinois Marching Illini performed what is considered to be the first halftime show, at a football game against the University of Chicago. Over the next few years, almost every university in the Midwest developed a marching band that could entertain the crowd during halftime of games, and before long the trend spread nationwide. The new "fad" caught on with high schools as well, and over the next decade or two, marching bands would spread to most high schools and universities in the United States.

Nor was marching and music limited only to schools: Starting in the 1930s, organizations such as Boy Scout troops, VFW (Veterans of Foreign Wars) chapters, and the American Legion began to organize their own marching bands as a service to the local community (i.e., to help keep kids “off the streets.”). Using no woodwinds, these groups featured only drums and brass bugles pitched in the key of G, and eventually became known as Drum and Bugle corps. Early drum corps maintained a military aesthetic, prioritizing uniformity and discipline over artistic visual design. Drill design during this era would have taken one of two primary forms:

Sequence chart from the late 1950s

Precision Drill

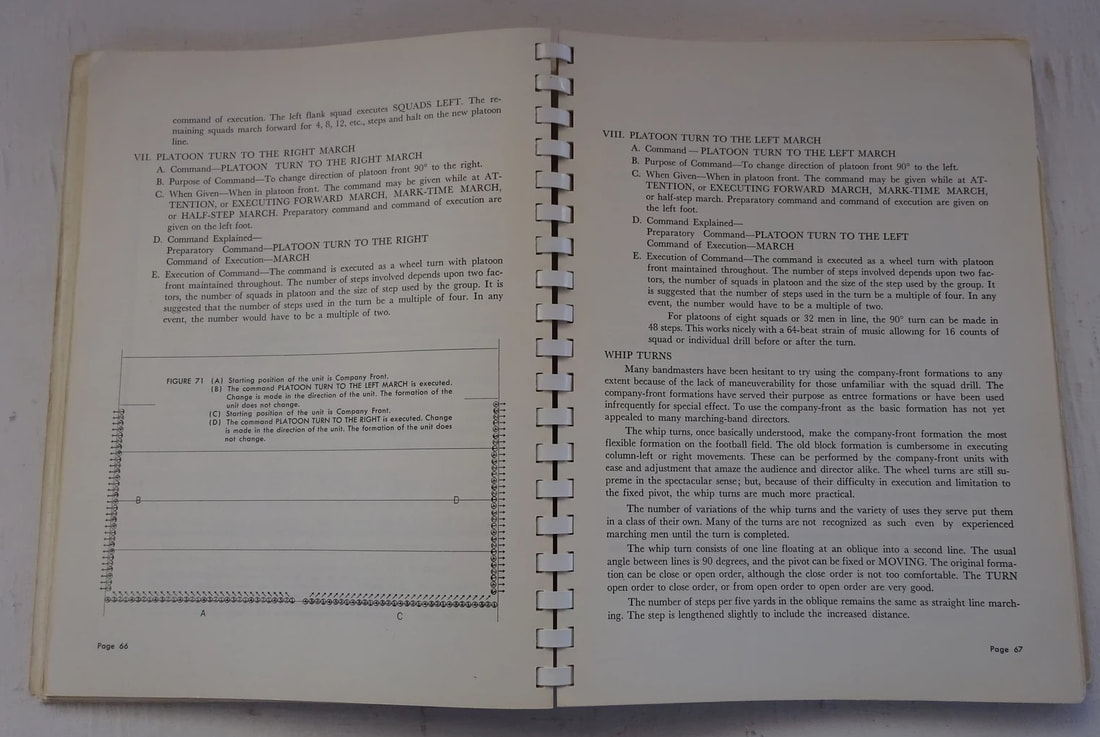

A.R. Casavant was one of the most influential figures in the transition to the more dynamic and expressive visual designs seen in modern marching bands and drum corps. His concepts challenged the rigid, symmetrical block formations of military-style bands as well as the chaotic, anarchic style of pageantry bands, paving the way for the fluid, musical storytelling that defines contemporary marching ensembles.

Casavant attended the Tennessee Military Institute (TMI) in Sweetwater, TN, where he studied business administration and led the school's regimental band. After graduating in 1938, he remained as an instructor while attending the University of Tennessee at Knoxville on a track scholarship. In 1938 he started the band program at McMinn County High School in nearby Athens, TN, later moving to Chattanooga High School. During this time, Casavant also led the local American Legion Post drum and bugle corp to a state marching championship in 1952 and 1953. During this time, he began to develop a method of marching and maneuvering that drew on the best that each existing drill style had to offer, and incorporated dance, theater, and art, with a focus on crisp geometric forms. His developing method was based on much research into various military styles, mathematics, physical education, and theatre. Casavant's "path vocabulary" (a method of getting from one place to another geometrically, without scattering) would come to be known as "Precision Drill." "Precision Drill is a concept of marching. It is a method to change the direction of a formation, to change the organization within the formation or to change from one formation to another. Precision Marching, or Precision Execution, refers to a standard of execution. Precision Execution is that execution that very few attain - the perfection of human uniformity in movement. Precision Marching is that execution when the difference in position and movement of individuals is not discernable [sic] by the human eye...above the tolerance of an experienced judge."

Examples from Casavant's "Precision Drill" textbook

Precision Drill became a sensation when Casavant's Chatanooga High School marching band performed on national television during a Washington Redskins home football game in 1955. Casavant would go on to author over 40 books on his method, and marching in general. At the end of the 1958-59 school year, demand was so great for Casavant's services around the country that he left Chattanooga High School to pursue clinical teaching full time.

The Rise of Competition

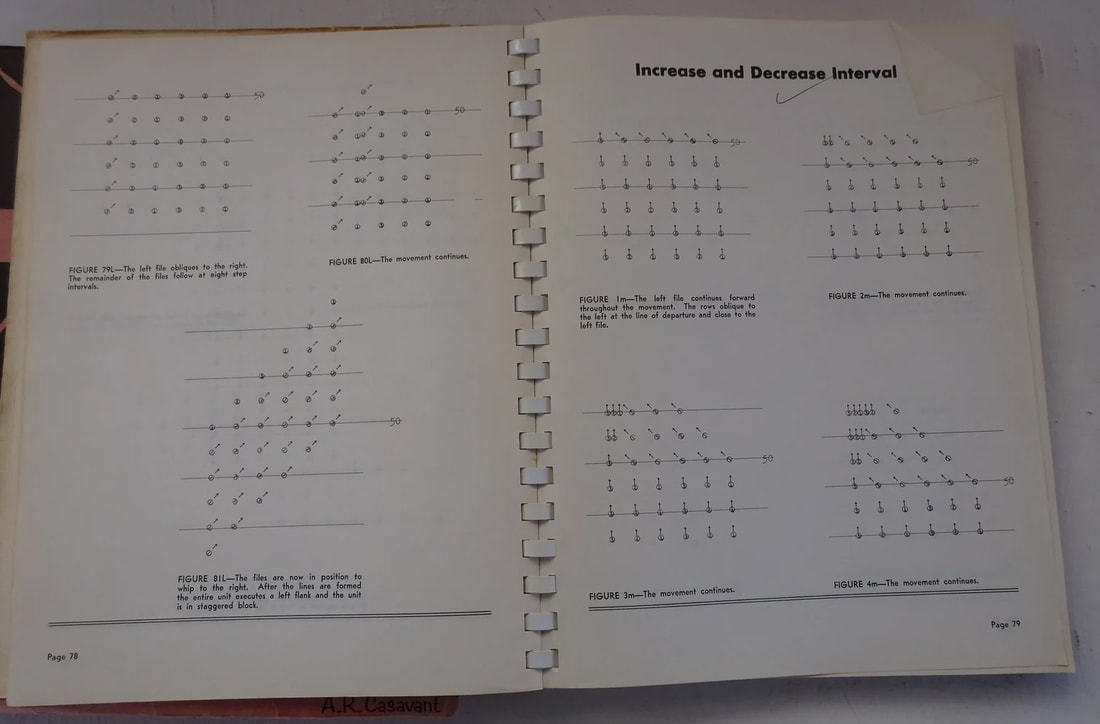

In the 1960s, Patterns of Motion became the de facto method for teaching and designing drill. This method was based on a constant-motion system using four-player squads marching 8 steps to every 5 yards, utilizing 22 and a half inch steps, at a 2 step interval. If you've ever seen an HBCU (Historically Black College/University) marching band, then you've seen something very closely related to Patterns of Motion.

Patterns of Motion Concept Drill

Created by Bill Moffit, who was band director at Michigan State University at the time, the approach was in stark contrast to the military style of marching in ranks, and performing flanks and column movements. Patterns of Motion revolutionized how college and high school marching band shows were designed and taught. It remained a popular style of drill design up until the late 1980s/1990s, when so-called "corps style" (and the rise of computer software which enabled it) surpassed it in popularity.

University of Houston marching Patterns of Motion drill

As marching band and drum corps competitions gained popularity, designers began exploring asymmetry, and curved formations began to appear, moving away from rigid squares and blocks. Diagonal movement became more common, allowing for greater visual motion, and drill writers began synchronizing movement with musical phrasing, laying the foundation for modern visual storytelling. A significant influence in this era was Pete Emmons, a designer with the Santa Clara Vanguard, who played a key role in breaking away from symmetrical formations and embracing more fluid, organic movement. Instead of merely moving from form to form, designers started to consider how the drill could enhance the music.

The formation of Drum Corps International (DCI) in 1972 created a new standard for visual performance, pushing designers to experiment with form, motion, and integration of the entire ensemble. The 1970s and 1980s marked the true revolution in drill design, led by visionary designers who redefined how ensembles moved on the field. Drill design shifted from being merely decorative to becoming a crucial component of the overall performance. The 1970s also saw the formation of Bands of America, then called Marching Bands of America, which further encouraged experimentation in high school marching bands. Shows became more theatrical, incorporating simple thematic elements that laid the foundation for future innovations..

Indiana State University Marching Band (1974) Pregame Drill

"The Golden Age" of the 80s and 90s

The 1980s and 1990s ushered in what many consider the golden age of drill design. With the DCI World Championships being regularly broadcast on PBS, drum corps shows became more widely accessible, inspiring high school and college marching bands to adopt more theatrical and innovative drill concepts. At the same time, Bands of America (BOA) was rapidly growing, turning into the premier high school marching competition circuit in the United States. With this increased exposure, designers were motivated to create more intricate and visually compelling shows, knowing their work would be seen by larger audiences beyond just those in stadiums.

One of the biggest game-changers of this era was the introduction of Pyware 3D Drill Design Software in 1982. Before this, drill writers wrote their drill manually, either meticulously charted on paper grids or, in some cases, improvised on the field with performers recording their individual coordinate points. This method was not only slow and time-consuming, but also limited the ability to experiment.

1991 Phantom Regiment handwritten drill design by John Brazale

With Pyware, designers could now

Pyware quickly became an essential tool for high school band directors and emerging drill writers, making advanced design concepts more accessible to ensembles beyond elite DCI drum corps or BOA bands. Full Disclosure: I am a long-time user of Pyware, and currently serve as one of their beta testers, but I began my career writing drill by hand (still have my old tools, see below), then transitioning to an old program called DrillQuest, before finally upgrading to Pyware in 2004.

Tools of the trade for marching band drill writers before Pyware

Another major shift in this era was the expanded role of the color guard. Previously, guards performed parallel to the band, often serving as a separate visual component. However, with the rise of theatrical storytelling in marching productions, guards became an intrinsic part of the overall design. Guard began to be integrated into the corps or band, either inside of forms (instead of always in the back or the sides), or actually becoming part of the formation, making them an active part of the overall field picture.

The use of props and elaborate equipment (such as rifles, sabers, and large-scale flags) were used to enhance visual storytelling, and guards saw an increased emphasis on dance and expressive movement, borrowing techniques from ballet and modern dance. The New Millennium: An Era of Storytelling

The 2000s saw an increasing level of demand for performers, while innovations and improvements to design software like Pyware revolutionized the creation and execution of visual shows. The geometric, dynamic designs of Michael Gaines for the Cavaliers emphasized athleticism and a seamless flow between musical phrases and visual storytelling. His design for the 2002 show Frameworks is often cited as a masterpiece of visual and musical integration (though my personal favourite of this era is his 2000 masterpiece, Niagara Falls).

Jay Murphy’s designs for the Blue Devils leaned into abstract, artistic representations, often focusing on thematic or conceptual shows rather than linear storytelling. His use of minimalist and modern aesthetics redefined the boundaries of what drum corps could convey visually. It's hard to argue with the results...the Blue Devils have racked up 11 of the 25 championships since the turn of the century. By the 2010s, drill design had evolved into a powerful storytelling tool. Both drum corps and marching bands embraced thematic productions, where every aspect of the show was designed to convey a unified concept. Drill was no longer just about formations, but was used to help mood and emotion, and shows continued to blur the lines between pageantry and theater. Designers began to borrow more heavily from other art forms, such as ballet, modern dance, and film. This was reflected in more expressive body movements and staging. While DCI is still considered a step above the best high school marching bands in the country, the distance between the two has narrowed, especially in the creative sense. High school bands continued to adopt many DCI-inspired techniques, but with an emphasis on accessibility for younger performers. BOA Championship Week features myriad bands who incorporate large-scale set pieces, projection screens, and lighting effects to enhance the visual storytelling. Movement is no longer limited to step-based marching…performers frequently run, dance, and interact with props, while integrating modern dance techniques and fluid motion, inspired by WGI (Winter Guard International) and contemporary ballet. Thematic storytelling has become central to BOA performances, with intricate props and large-scale visual effects dominating shows. In many cases (though I am sure some wouldn't admit it), innovations in BOA performances actually influenced DCI instead of the other way around. The fact that many designers work with DCI and BOA (and WGI) groups helps blur those lines. Drill design now integrates elements of dance and acrobatics, requiring performers to be both musicians and athletes. High-speed direction changes, body movements, and prop manipulation demand advanced training, and must be planned meticulously by the drill designer in conjunction with the creative team. Design has also focused more on dynamic staging, where performers are often grouped in smaller pods or scatter forms to emphasize intimacy and individuality. Straight lines and geometric shapes are still used, but often as contrasts to the more organic forms.

Drill Chart designed with Pyware

Conclusion: Where do we go now?

The evolution of drill design for marching band and drum corps reflects a continuous push for artistic excellence, technical innovation, and emotional storytelling. From its military origins to its current status as a blend of pageantry, theater, and athleticism, the activity has transformed into a breathtaking visual and musical spectacle.

As technology advances and designers seek new ways to engage audiences, the future of drill design promises even greater creativity, complexity, and emotional depth. Looking ahead, we can expect even more experimentation with staging, visual effects, and interdisciplinary influences. Whether through the seamless integration of props, enhanced storytelling, or entirely new staging techniques, one thing is certain...the evolution of marching band and drum corps drill design is far from over. Thanks for reading. If you or someone you know needs Custom Marching Band Drill Design for your band, please consider using me! |

MeMusician. Educator. Conductor. Archives

April 2025

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed