|

A few weeks ago, I was invited to share my insights on arranging music for marching bands with a Marching Band Techniques class at Western Illinois University. Reflecting on the evolution in my style over the past 25 years, I decided to summarize my presentation into a blog post, figuring that it might be of interest to others, so...here's a bit of a deep dive into the art - and science - of arranging music for marching bands. The specific example I used in my lecture was my arrangement of the Smashing Pumpkins' 1996 hit, "Tonight, Tonight." It's a song I've always enjoyed, making the arrangement process a pleasure rather than a chore. Arranging music you like can significantly enhance your work quality and enjoyment. Even though I take on all kinds of projects, there's a special joy in working on tunes you can listen to repeatedly. If you don't know the tune, take a moment to listen to it - you may find that you've heard it before, though you may not have known its name or who performed it: "Tonight, Tonight," from the album Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness THE FOUNDATION: LISTENING and TRANSCRIBING When arranging, especially without a provided score or lead sheet, the process begins by listening to the original tune multiple times to capture the correct melody, rhythms, and harmonies. From teaching courses on orchestration for years, I'm well aware that MIDI versions of many pop and rock songs can be found online, and that many student arrangers are drawn to using these because it cuts down on the amount of work. Unfortunately, this also robs students of an opportunity to use their ears critically, an invaluable skill in arranging. I myself prefer working from a reliable score/lead sheet or directly transcribing by ear to avoid inaccuracies - too often I've seen MIDI files that have contained numerous errors in rhythm, harmony, and sometimes even the melody itself! For tricky sections, especially in faster music, I will sometimes use software like Amazing Slowdowner, which allows me to slow down the music without altering the pitch. This helps in catching any complex rhythms or pitches I might miss at full speed. Sometimes, I'll also adjust the pitch to better fit the desired key for the arrangement. After thoroughly familiarizing myself with the tune, I begin inputting the melody into Finale, sometimes using the piano* for help with complex passages or harmonies. I then create a 5-line sketch of the arrangement. This sketch helps streamline the structure (see below), especially when dealing with longer songs that need to be condensed into a 1:30 to 2:00 marching band arrangement. *I recently had to use the piano for an arrangement of a fun-but-silly tune by Thank You Scientist, which had very complex and rapid passages in the middle section. Here is how that one turned out, in case you're curious. SELECTING YOUR STRUCTURE One of the trickiest parts of arranging pop or rock music for marching bands is deciding which sections to cut. Pop and rock songs are famous for their catchy repeated verses, choruses, and hooks, but that repetition doesn't translate well to marching band performances, especially when the original song is longer than two minutes. Here is where my own biases come into play: While I have certainly enjoyed arrangements that present a very different "take" on the music being arranged, when it comes to rock and pop music, my preference is to stay as faithful to the original as I can. These types of arrangements are typically not used in competitive marching band shows (although there are plenty of examples of successful uses of pop/rock music in BOA-type shows), but are most often presented by bands seeking to entertain a football crowd on Friday nights. A conversation I once had with a well-meaning (but somewhat blunt) football dad convinced me that arrangers sometimes outthink themselves when it comes to arranging pop and rock music. Most of the time, the audience simply wants to be able to recognise the song being performed. My high school band was performing an arrangement that took various wild liberties with the music. It was not well-received by the 99% football crowd. I guess the previous two paragraphs can be summarized by saying: Know your audience. Typically, I approach the topic of song structure by first identifying each section. I try to always use the song's intro, especially if it's short and impactful. Repeated verses are usually presented just once, or at most twice if the song's structure really demands it. Choruses are included once or twice, but other song structures like breaks or interludes (think of those classic 1980s guitar solos) are often left out, though they can sometimes be used to great effect if you have a wind soloist that is capable, or even a guitar or keyboard player in the pit. Refrains and bridges are used on a case-by-case basis. Remember, most marching band arrangements need to fit within a 1:30 to 2:00 timeframe, so significant editing will often be necessary, especially for longer songs like "Tonight, Tonight." To create a cohesive arrangement, I start with a 5-line sketch that includes the song's intro, a verse or two, a chorus or two, and a coda or ending. This process can be challenging, especially with 1980s music where many songs end with fades that don't work in a marching band context. My sketches typically contain two treble clef lines, two bass clef lines, and a basic drumset part. This helps me think about the rhythmic elements and how to incorporate drum parts later on. Here is a glimpse into my initial sketch for "Tonight, Tonight": Initial 5-line Sketch, "Tonight, Tonight" As you can see/hear, I ended up cutting out a few of the more repetitive sections, though I knew right away I wanted to use that arpeggiated guitar lick that starts at 0:38 in the original...but how best to do it? And for that matter, how can we get the majestic full sound of the introduction, while also musically portraying the softer verses? This is where orchestration enters the picture. THE ART OF ORCHESTRATION Orchestration is crucial for a compelling arrangement. Understanding what each instrument can and cannot do, and where they sound best, is essential. Early in my career, much of this was trial and error for me, but now I rely on a solid grasp of instrument capabilities. This was not always the case...I still keep a handful of arrangements I did early in my career that I keep as a reminder to myself of how much I've learned (one chart in particular had 3 different flute parts, 3 different clarinet parts, 3 alto sax parts, 2 tenor sax parts, 3 mellophone parts, and also featured intricate rhythms that would be near impossible to clean for use on a marching field). Since then, I've found more success employing the "less-is-more" philosophy of instrumentation. Unless you've got a huge, huge band with tons of woodwinds, it doesn't make a lot of sense to split parts that much. Most music you arrange is going to have only 4-6 different things happening at once (unless of course you are arranging Rite of Spring). Here’s a typical breakdown I use for marching band instrumentation:

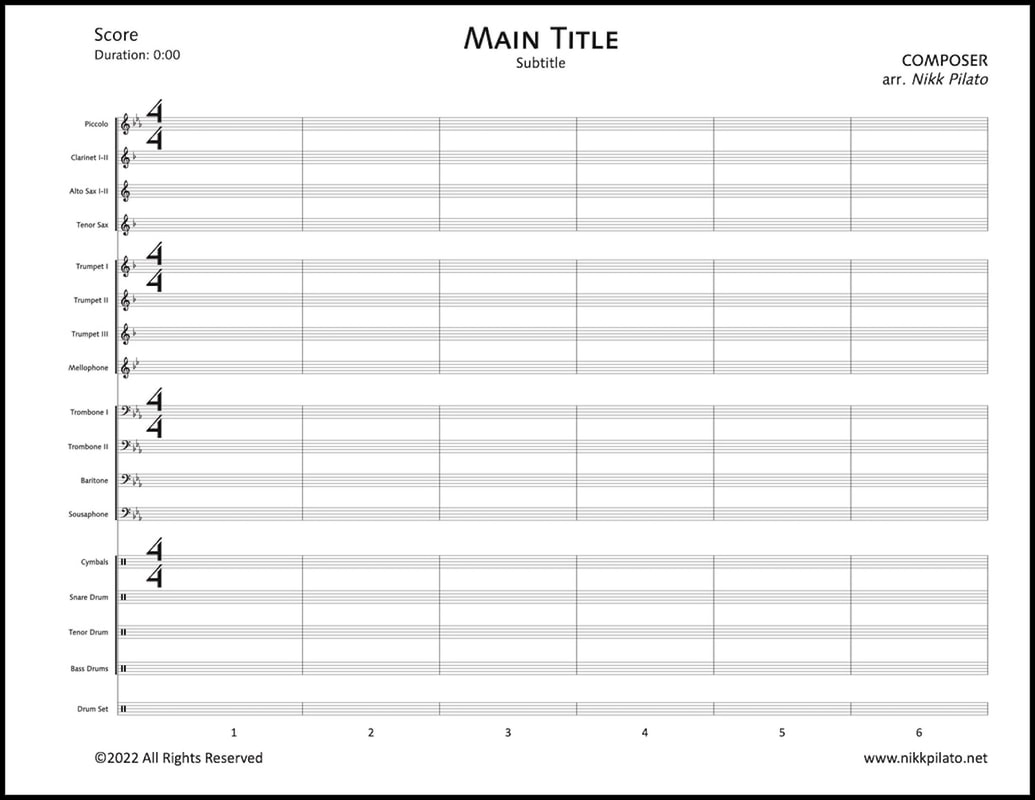

Successful combinations include Alto Saxes with Mellophones, Tenor Saxes with Trombones, Tenor Saxes with Baritones, Trumpets and Flutes/Piccolos, Trumpets and Alto Saxes, Clarinets and Mellophones, Clarinets and Baritones, and many more, depending on the colour you want from the group. Each combination needs careful consideration of their roles and dynamics to ensure a balanced sound. One way you can learn about this is by studying other arrangers' work. From the great Tom Wallace (you've no doubt played some of his charts...he is also the staff arranger for the University of Georgia Redcoat Marching Band) I learned to use the trombones/baritones as a harmonic foundation. His arrangements feature lush, 3- and 4-part harmony using the low brass that is just hard to beat. From Jay Bocook I learned how to use the woodwinds in a way that will ensure they are heard. From Jay Dawson I learned how to add to a melody so that the end result is that the melody is heard more prominently...even when you haven't changed anything about it by itself. And from myriad great arrangers out there, I learned about using middle voices for acrobatic countermelodies. If you're not familiar with instrument ranges and tessituras, I highly suggest taking an orchestration or instrumentation course (if you're still in college), or picking up a book on those topics. For me, discovering Kennan's/Grantham's "The Technique of Orchestration" in college was a game-changer. I read it cover-to-cover, and it helped me truly understand the ranges of the instruments, where they sound great, how best to combine them, etc. Definitely worth picking up (especially if you can find an earlier edition that doesn't cost as much as the later ones). Using notation software (Finale, in my case), I set up a template that includes the layout I prefer, my preferred fonts, my preferred expressions and articulations, and the correct playback sounds for each instrument (I use NotePerformer for my wind instrument sounds, and Virtual Drumline for the percussion sounds). The template allows me to work quickly during the summer months, when I might have a slew of music to arrange...not having to start from scratch with every project is a time-saver. After my sketch is complete, I will start orchestrating it. The introduction of the original song is loud and full, the usual guitar, bass guitar, and drums augmented by strings. This allows me to use all the voices tutti for a strong initial impression right off the bat. (A word about the percussion: I am not a percussionist. I've been teaching myself how to write for a battery section, but it will never be fluid for me...still, I enjoy creating these parts and trying to make them as playable as possible, because there are bands out there that can't afford to hire a drumline arranger. I expect that most people who would purchase one of my arrangements would indeed have someone that would write their own parts - or at least mercilessly edit mine) Introduction Moving on from the introduction, we come to the verses. As I said earlier, I knew I wanted to use the arpeggiated guitar riff, so I decided to use it as an alternating motive between clarinets + mellophone and piccolo/flute + alto sax. I also included cues in the trumpet, just in case. Billy Corgan's voice lends itself well to the low brass, so that's where I put most of the melody from the verses (also, because I am using upper voices to replicate the guitar riff): Verse 1 I do repeat the verse in my arrangement, with a slightly modified conclusion the second time around, then I hit the ending riff, where several things are happening at once...I liked the chaotic feel of this section of the song. I knew I wanted to replicate the ending, which has a very classic 80s/90s soft ending aesthetic, but I realised it would be difficult to orchestrate...unless I did it as a solo with only partial woodwind accompaniment, at least until the solid power chords at the end. My students at ISU were fond of waving "fake lighters" in the air, like you'd often see from concert audiences in the 80s and 90s, which always made me chuckle. Coda/Ending Section There were tweaks after I completed it, to be sure. One of the healthier habits I've gotten into is to set aside a finished arrangement for at least 24 hours, so I can come back to it with fresh eyes and ears. Doing this has saved me from making silly mistakes, and more than a few times has also allowed a new orchestrational idea to percolate during my down time, helping me to improve the arrangement. I highly recommend this strategy to anyone who is writing any sort of arrangement. Since I've given you examples of my process and used the actual Finale playback for them, a note of caution about these types of playback files: Notation programs play back everything with mechanical precision. They will "overcome" your mistakes - for example, if you write a flute part in the bottom part of the staff and expect to hear it on the field, you better have them amplified, or have no one else playing (even then, you may not hear them!) However, a notation program will play it back and it will be audible, fooling you into thinking that all is well. This is where your "inner ear" becomes indispensable. Full finished arrangement DEVELOPING YOUR INNER EAR Developing the ability to audiate, or hear the music internally, helps you anticipate how combinations of instruments will sound in different ranges and dynamics. It will also help you avoid balance issues like the ones described above. The more you practice audiating, the better your ear will get. After some time, you will start to "hear" what combinations of instruments sound like, how they work in whatever range you are trying to write them in, whether or not they will be muddy or sharp, clear or obscured, loud or soft, etc. All without the need to have the software play it back for you. Try this right now...think of a trumpet's sound. "Picture" them playing a note, any note, at a mezzo forte level. Can you hear that note in your head? Can you hear it crescendo, then decrescendo? Can you hear it articulating a staccato, a marcato, a martellato? Now...add an alto saxophone to this sound, playing in unison with the trumpet. Can you hear the combination of their sounds? Can you hear them play four quarter notes together? Test yourself by adding other instruments, or different combinations. If you find that easy, try hearing a trumpet playing a simple melody, while a mellophone plays the harmony a third below...if you found that difficult, that's ok. Audiation is a skill that has to be practiced and honed, like any other musical skill. If you want to be a conductor of any kind, it is also a skill you will find indispensable when it comes to score study and rehearsing an ensemble...might as well get a head start now! FINAL THOUGHTS

Arranging music for marching bands combines technical skills with creative artistry. Whether you're cutting sections to fit time constraints or carefully choosing instrument combinations, each step requires attention to detail and a deep understanding of both the music and the ensemble. By embracing these principles and continually honing your skills, you can create engaging and memorable marching band arrangements. Got a specific question? Feel free to comment below, and I'll do my best to check in and answer. Remember, the ultimate goal is to bring the music to life in a way that resonates with both the performers and the audience. Happy arranging! - - - If you are interested in purchasing the arrangement discussed in this post, or any other arrangement, please visit this page. If you are in need of a custom arrangement, I am happy to help there too! Contact me for details. |

MeMusician. Educator. Conductor. Archives

April 2025

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed