|

DISCLAIMER Please note: I am not a copyright lawyer. I've done research into copyright for years, and have had conversations with copyright lawyers, but the law is always changing - sometimes even too fast for those who live in that world. Please take everything you read here with a large grain of salt, and always err on the side of caution. If you see something in this post that has been inadvertently misrepresented, please let me know and I will gladly edit or remove it. Copyright DefinedCopyright is the legal right granted to the creator of an original work, allowing them exclusive control over its use and distribution for a specified period of time. This right enables creators to benefit financially from their creations, fostering innovation and artistic expression. Copyright is just one form of intellectual property...other forms of include patents, trademarks, trade dress (the packaging and labeling of protected products, the layout of a particular restaurant), trade secrets (the formula of Coca-Cola, the KFC original recipe), industrial design rights, and plant breeder rights. For a work to be eligible for copyright protection, it must be "fixed in a tangible medium," meaning it must be recorded in some form, whether written, recorded, or otherwise captured. Importantly, copyright does not protect ideas, thoughts, or casual conversations - it only protects the expression of those ideas in a fixed form. Additionally, the work must be original and exhibit some level of creativity ( (in other words, you cannot copyright a work consisting of dry facts organized in a conventional way - this was tested in the courtroom when a phone company tried to copyright the phone book, and failed). Copyright Law in the USIn the United States, the first law governing intellectual rights was the Copyright Act of 1790, the stated object of which was to secure for authors the "sole right and liberty of printing, reprinting, publishing and vending" the copies of their creations. Thus, the main function of the Copyright Act of 1790 was to encourage creativity and the development of a national art, music, and literature – all important things in a country that was a mere child on the international stage, and had very little of the above. Ironically, the Act was copied almost verbatim from the "Statute of Anne," an English edict sometimes known as the Copyright Act of 1710, which is considered the world's first government-enforced protection for creators of content. The initial Act did not cover musical compositions. These were addressed in the Copyright Act of 1831, but until then, most musical compositions were registered as books. Until this law was passed, a creator of content had no legal recourse if someone stole their work. Any publisher or book seller - or anyone who owned a printing press - could simply run off copies of any book or sheet music they wanted, and make money from the creative efforts of others (denying those people an opportunity to benefit financially from their own creations). The Copyright Act of 1790 granted copyright protection to maps, charts, and books for a period of 14 years, with the right to renew for one additional 14-year term…if the copyright holder was still alive at the end of the first term, for a total of 28 years. The Copyright Act of 1831 revised that to 28 years plus an optional 14-year extension for a total of 42 years. The Copyright Act of 1909 revised that to 28 years plus an optional 28-year extension for a total of 56 years. The Copyright Act of 1976 revised that yet again, to “lifetime of the author plus 50 years.” And finally, the Copyright Term Extension Act of 1998 (sometimes referred to as the Sonny Bono act, or more derisively, the "Mickey Mouse Protection Act) revised that to “lifetime of the author plus 70 years” for general copyright, or 95 years from publication/120 years from creation (whichever comes first) for works-for-hire. One might well wonder why an author, composer, poet, or playwright would need a copyright of over 100 years, when the typical life expectancy of a human being is 74 years…the truth is, most of these copyright extensions were pursued not by individuals, but by corporations, some of which have lobbied hard to extend the law because their profits depend on keeping their “properties” under copyright. One company in particular has been lobbying for more and more copyright protection, including the possibility of a perpetual copyright that would never expire (which is ironic, since the bulk of their profits came from works that were in the Public Domain at the time)…you'll never guess who... The Public DomainAfter the period of copyright exclusivity ends, the work is supposed to enter into the Public Domain, where it now belongs to everyone, and is free for all to use. As of the writing of this blog post, any work created in 1928 or prior is considered to be in the public domain. Some examples of public domain works include:

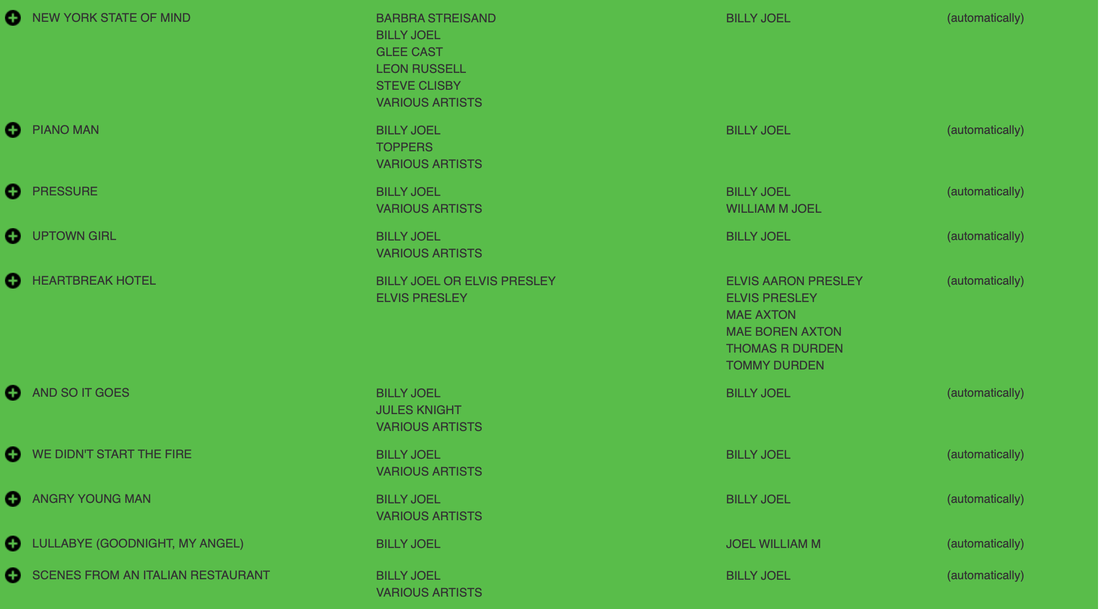

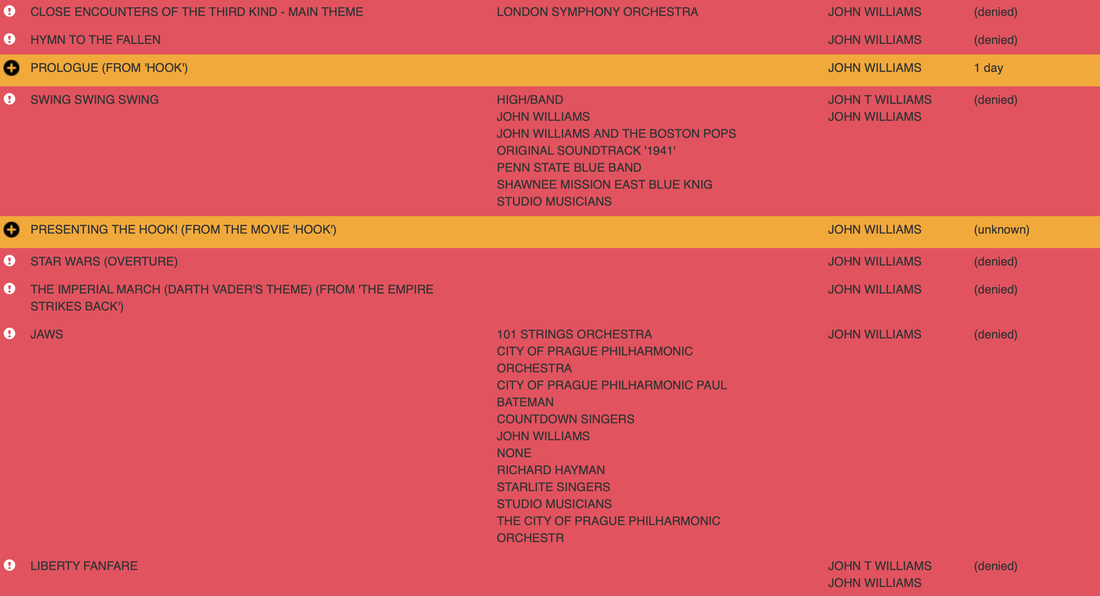

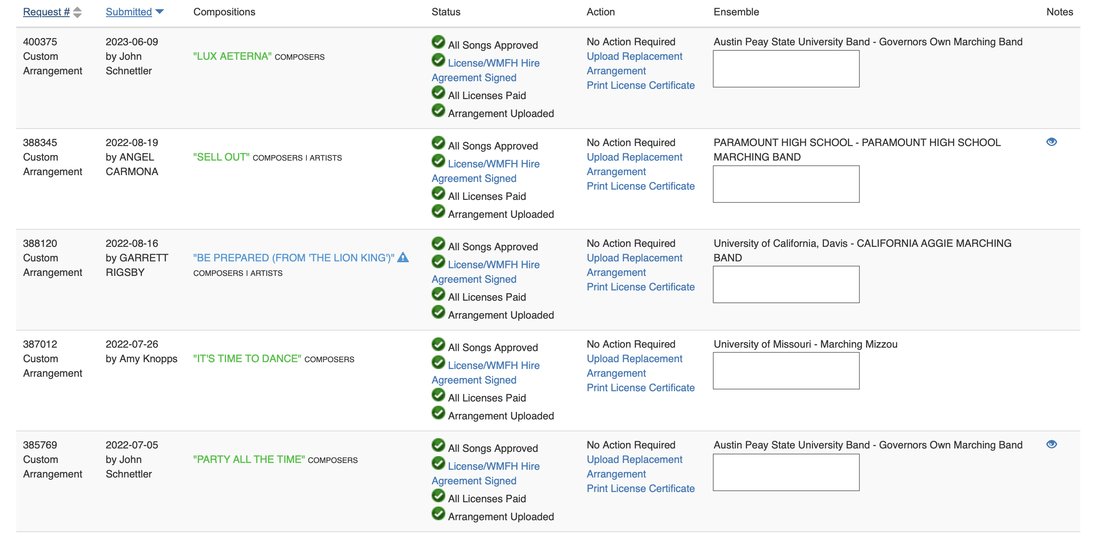

Music in the public domain can be reproduced, copied, or arranged without worrying about having to pay royalties. It is an open resource for arrangements and ideas for new works. Arranging anything based on the music of Classical or Romantic composers is fair game. Even some really great works from the early 20th Century are considered to be in the public domain (though you should always double check). Be careful to use only the original public domain works if you want to arrange them or use them in some fashion. For example: Bizet's "Carmen" is in the public domain…but if you were to arrange the Yo Goto version of Carmen (for wind band), you would be infringing on the derivative rights of the arranger (Goto), even though the original work itself is public domain. Securing CopyrightIn the world of marching bands and show choirs (the two most frequent "abusers" of copyright), many directors purchase stock music arrangements because they are inexpensive (and incur no further licensing costs), though sometimes directors may wish for customized arrangements, which require a few extra steps… If you want to use a copyrighted piece of music in your marching band show or indoor routine, then you need to secure permission via an arrangement license. Technically speaking, even adding new drum parts to an already existing marching band arrangement, or adding instruments to an a cappella choral work, would require an arrangement license. However, this is one of those grey areas that most rights holders seem to overlook or ignore. Entities such as DCI, WGI, and BOA will check the status of your permissions when entering major regional competitions. Often, you must have not only permission to arrange, but also mechanical and synchronization permissions. State-sponsored organizations and contests are somewhat more lenient about checking to see if you have secured the proper copyrights…but more and more of them are beginning to check more rigorously to avoid culpability. The process for requesting permission varies from publisher to publisher, with some taking as little as a minute to grant permission via an automated process, and some taking up to six months to grant (or deny) permission to arrange! Some services also have a pre-cleared list of tunes that are immediately licensed. There are also some companies that will take care of the process for you...for a fee. Some publishers insist that you go through one of these "middle men," but if you are looking to save money and have some extra time for research, you can often contact a publisher, estate, or rights holder directly and secure a proper license through them. John Mackey is a good example of a composer who handles his own copyright permissions...all you have to do is contact him instead of going through a third party company, who is going to charge you an extra fee. Costs are going to vary wildly, depending on the publisher, the artist, the size of your group, and the intended use of the arrangement. Some licenses cost as little as $100, and some can cost as much as several thousands for a single work. In general, you should expect to pay between $200 and $500 per chart or song. If you are creating a medley, costs will be higher. Take heed, though: Some composers and/or rights holders will NOT give permission for some or all of their music. Examples of this include John Williams, David Maslanka, Thomas Newman, Charles Ives, Vincent Persichetti, all Nintendo music, much Disney music, and several others…BOA used to keep a list of all music that was likely to be denied, called the "Do Not Arrange" list...they don't seem to keep that list anymore. As a bit of a personal anecdote...a few decades ago I had a conversation with the composer Ron Nelson about his piece Rocky Point Holiday. Near the end of the conversation, I couldn't resist asking him about the drum corps "urban legend" that he had sued the Garfield Cadets for infringement in the early 1980s. While he played coy about the details, he did recount to me that he happened to be watching DCI Finals on PBS when he heard a "mashup" of Bernstein's Mass and his own Rocky Point Holiday. Since had never been asked permission to use the tune, he was annoyed, and let it be known through his lawyer. He told me that from that point on, to discourage corps from using his music, he decided to charge an "exorbitant" fee (which I believe I remember was $1500 at the time...seems rather quaint today). He said that no one bothered him with an arrangement permission request until 1991, when the Blue Knights happily paid the fee for "Savannah River Holiday." He gave up on trying to restrict his music after that. In any case, the result of not following proper procedure can result in a lawsuit against you personally, the ensemble or school you work for, or BOTH. There are cases that have resulted in fines of thousands of dollars, and directors have lost their employment. New music is the result of ensembles purchasing and performing published works and properly following copyright laws. If we want to see the continued development of great works, we must continue to respect the process. Fair Use“Fair Use” is by far one of the most misunderstood concepts involved in copyright. Fair use is determined using the following criteria:

These criteria were intentionally left vague by Congress to allow for flexibility in the face of new technologies yet to come. But when ordinary users cannot determine whether a proposed use is fair, rights holders are able to assert that ANY use would constitute infringement, which is not how the law was intended to function. According to Jason Mazzone, law professor at the University of Illinois, while the law intended to set a minimum amount of copying as fair use, many rights holders have decided to use this as a maximum fair use ceiling. The result of this is that fair use is being unfairly (and illegally) constrained instead of encouraged. The very vagueness in the law that allows for flexibility also leaves room for aggressive overreach on the part of corporations and publishers. How often have you read the notice “Any photocopying of this publication is illegal” or “permission for duplication, for any purpose, must be secured from the copyright owner?” This is the publishing industry’s boilerplate attempt to limit ALL copying, fair or not. It is also not true, as the guidelines from Congress have laid out several instances where copying is allowed. If the Music Publishers Association’s position were the actual law, then there would be no such thing as Fair Use. The whole purpose of Fair Use is to be able to use works without obtaining permission beforehand. What you CAN do...

What you CANNOT do...

As I said at the very start - I am not a lawyer. I've done my best to give accurate information, but none of the above should be considered legal advice. I may not be a lawyer, but I AM a music arranger...and if you are in need of custom music arrangements, public domain or otherwise, I am always happy to put my skills to use.

|

MeMusician. Educator. Conductor. Archives

April 2025

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed