|

INTRODUCTION Playing with good intonation in an ensemble setting is a performance skill. It must be practiced diligently, just as you would practice scales, sight-reading, multiple tonguing, etc. Unfortunately, few of us practice “being in tune,” either because of an ignorance of its importance, or because of confusion on how best to proceed. The result is that over the course of a typical rehearsal, numerous unison lines remain out of tune, chords do not “ring true,” and performers do not get the best possible sound out of their instruments. Good intonation presupposes two ideas:

This entry will offer suggestions for training and improvement on both counts. As with anything else I ever post here, the subject material is drawn from myriad sources, including published research, colleague and mentor/teacher opinions, and experience conducting ensembles for the past twenty-five years. There is also a wealth of information to be found on YouTube - provided you can adequately sift through the information to find the important nuggets. However, this is not intended to be "the final word" regarding intonation - if you have anything to contribute, be it a correction, an emendation, or an addition, please don't be shy about replying and/or emailing me. I've been studying intonation for a long time, but will never fully master all there is to learn, and am always open to new ideas and opinions. FACTORS THAT CAUSE POOR INTONATION It is important to understand why poor intonation is so prevalent. The following areas of concern can cause poor intonation by themselves, though they are (unfortunately) usually paired with other factors: The Instrument/The Mouthpiece

Basic Playing Procedures

Not Playing in the Standard Tuning Frequency

Insufficient Warm-up Time

Psychological/Musical Phenomena

Pitch Tendencies of Instruments and Performers

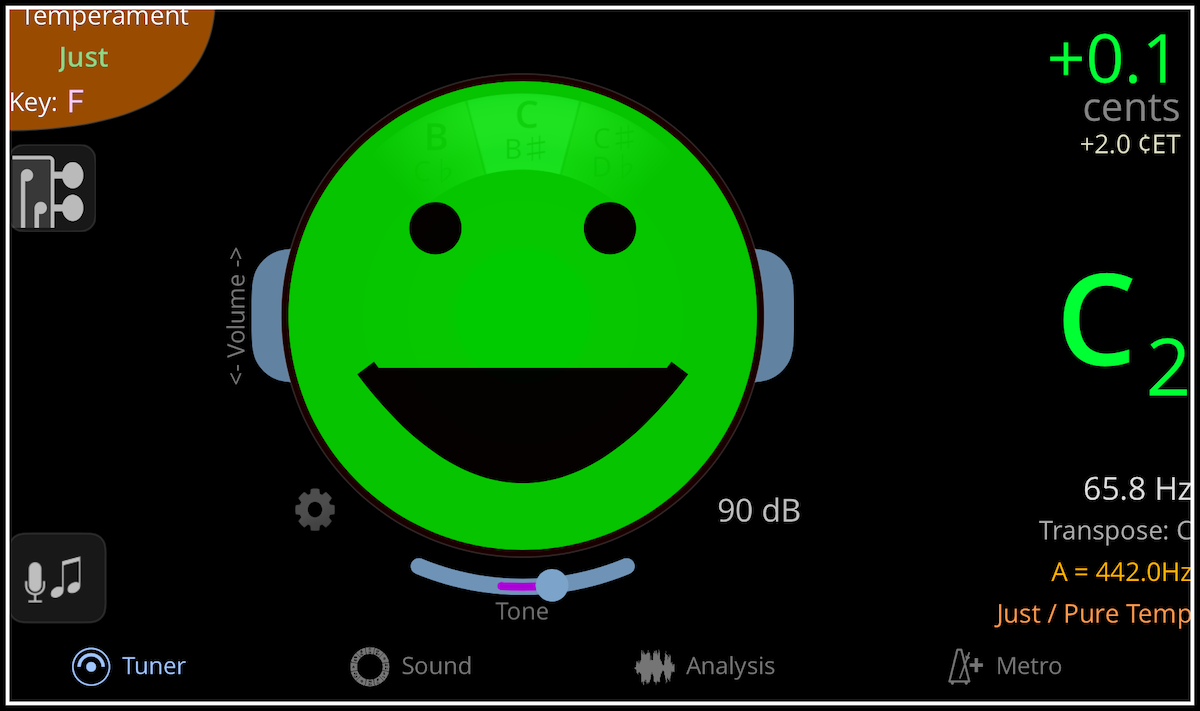

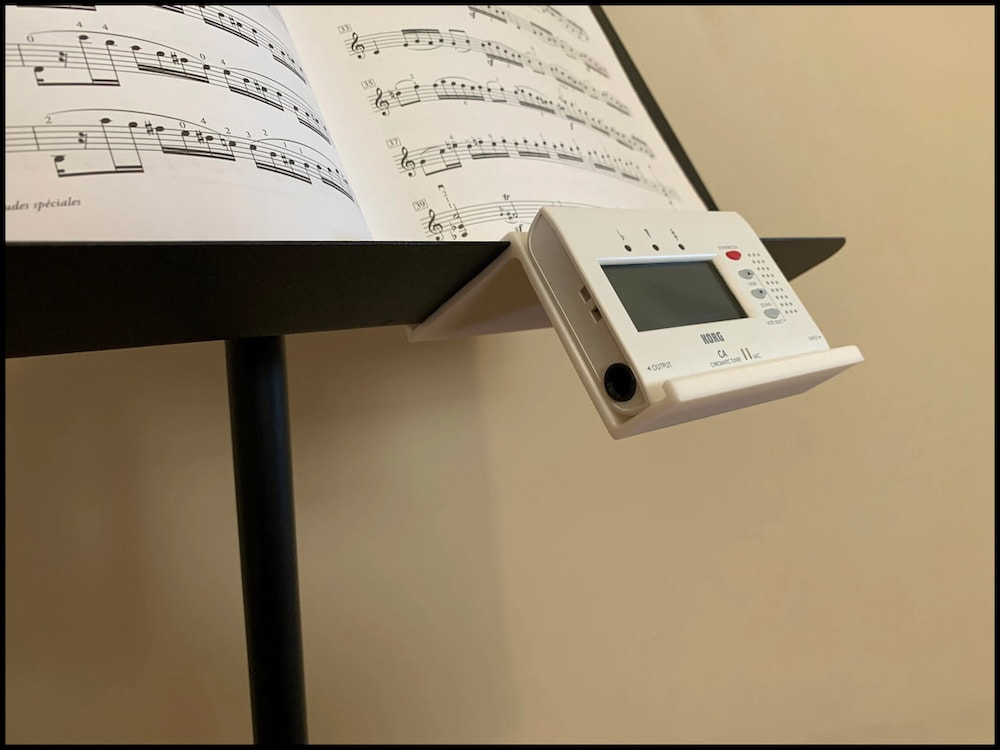

THE TUNING PROCESS With the exception of oboes and bassoons, wind instruments are manufactured to play sharp when the headpiece, tuning joints, or slides are closed/pushed in. Therefore, players must lengthen their instrument by pulling out the main tuning mechanism, whatever it is for that instrument. When tuning in an ensemble setting, the following basic procedures should be followed by all wind players:

THE HARMONIC SERIES The Harmonic Series is a naturally occurring (i.e., not man-made) acoustic and mathematical phenomenon that is the underlying foundation for the construction of sound on string, woodwind, and brass instruments. The series consists of frequencies (pitches) that are related to each other via whole number ratios of the lowest possible frequency, which is known as the fundamental. For example, if the fundamental was 10Hz, then 20Hz (2xF), 30Hz (3xF), 50Hz (5xF), and 100 Hz (10xF), would allbe harmonic frequencies of the fundamental. 55 Hz would not be a part of the harmonic series, because it is not a whole number ratio to the fundamental (5.5xF). 55Hz would, however, be a part of the harmonic series if the fundamental were 11Hz. These frequencies, known as harmonics, are possible because of complex vibrations. All freely vibrating bodies (such as a piano string or an air column) vibrate not just along their entire length, but also in halves, thirds, fourths, etc., theoretically onward into infinity. The smaller each segment of string (or air column) vibrates, the higher the frequency (pitch) produced above its fundamental, hence the name we often use synonymously with harmonics: overtones. Many of these overtones are inaudible to the human ear (just as many of the secondary vibrations are invisible to the eye). The lower the note played, the more obvious the overtones to our ears. This is why low notes on the piano, for example, tend to have such a vibrant and rich quality (try it out next time you are in a practice room...strike the lowest keys on the piano and strive to listen for the audible harmonics, particularly the fifth and the third of the fundamental). As we progress up the Harmonic Series, the intervals between overtones get smaller and smaller (and some are not even intervals that we use in Western music). Any sound we hear contains all the notes in its harmonic series to varying degrees. That variability is the reason that instruments playing the same pitch sound different: Their harmonics have different strengths. For example, an oboe playing A440 has a rich, reedy, spicy sound, while a clarinet playing the same note has a much less vibrant tone, simply because the clarinet’s construction suppresses some of the overtones (the 2nd, 4th, and 6th especially) that would make it stand out more. No matter how many overtones are present and audible, our ears tend to resolve all harmonically-related frequency components into a single sensation. Rather than perceiving all of the individual harmonics of a musical tone, we perceive them together as one pitch (the lowest one, or fundamental). Incredibly, this will happen if we hear just a few tones from the harmonic series…even if the fundamental is not actually sounding! This phenomenon is used in music recording, especially in low bass tones that are to be reproduced on small speakers such as earbuds or other headphones, and it fools your brain completely into thinking that the lowest tone is there, when in fact it is not. Yet another name often applied to the phenomenon of the harmonic series is partials. This is especially the case when speaking of the harmonic series in relation to brass instruments. For all intents and purposes, the terms harmonics, overtones, and partials are all interchangeable in this document. For brass players, these partials are particularly important, as they are the foundation to playing chromatically. Here are the first sixteen partials of the harmonic series (keep in mind that these partials go on, theoretically, into infinity):

If you were paying attention, you may have noticed that the first six partials of the harmonic series make up a Major Chord. In fact, many historians and theoreticians believe that the reason our harmony tends to be so heavily reliant on fifths, fourths, and thirds (i.e., major and minor chords) is because those are the most audible harmonics to the human ear. (This does not, however, explain why Asian and Arabic cultures use different harmonic models since they too would be able to hear the same harmonics as Western Europeans during the development of music). Here are some other tips/tricks that will help you learn harmonics/partials:

So why is any of this important to you? Well, knowledge of the harmonic series is how fingerings on brass, woodwind, and stringed instruments are derived. This knowledge could help you devise alternate fingerings for a troublesome spot, or decide a different way to voice a chord so that it sounds better in tune. But really, it is important to know because it is what music is all about, and knowledge for the sake of knowledge is still important. Knowing what we know now, we can see that the pitch “G,” for example, can be:

= = = “Every bit of playing we do today, be it good, bad, or indifferent, goes toward deciding what sort of player we will be tomorrow. A player who begins his day with a load of thoughtless, shoddy flourishes is simply perfecting their faults. Time spent trying to do simple things well is like putting money in the bank. Use your warmup time to do simple things well.” – John Fletcher |

MeMusician. Educator. Conductor. Archives

April 2025

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed